THE PERPETUITY OF RUIN

22 JUNE - 3 AUGUST 2017

FIELDWORKS GALLERY, LONDON

THE PERPETUITY OF RUIN

Throughout Bailey-Barker’s life he has collected objects from natural and man-made environments. Varying from Neolithic tools to contemporary refuse, some have value historically, culturally, emotionally, whilst others are simply interesting for their form or materiality. These objects have been collected from house-clearances, mudlarking, found in wildernesses and junk yards. He is particularly fascinated by tools and the way they have been animated and revered over time.

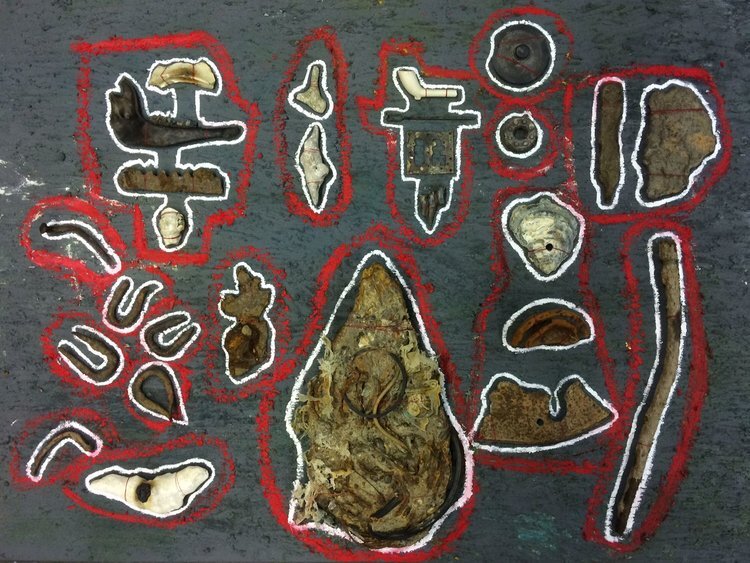

Bailey-Barker refers to his findings as route objects as they inform his abstract sculptures, which in turn function as new sacred forms, taking on the mythic qualities of the objects they draw from. Each sculpture is born from a ritual: finding a route object, excavating and observing, living with the object, categorising and assembling, extracting or imbuing narrative; resulting in an endless performance.

For example: 17th Century Pipe + flint arrowhead + goldfinch nest + axe once owned by the recently deceased Dr John Slome + crow skull + metal shard = sculpture number 88 (Peripheral Form).

Until recently the route objects behind Bailey-Barker’s practice have been concealed and sculptures have been exhibited without their corresponding equation of found objects. In THE PERPETUITY OF RUIN,Bailey-Barker reveals the equation behind his sculptural process, presenting an immersive installation and a new series of tapestries in which route objects are assembled, categorised and sewn onto canvas.

The objects amassed in these works include both certified antiques and fakes calling into question the importance of authenticity in historical relics. Does it matter if an antiquity is real if it points to a true notion of history? Can we identify the facsimile and the genuine? Is there an inherent quality specific to the real?

The works presented in this exhibition have been amalgamated over 20 years. Objects found in the artist’s childhood and previously cherished are displayed beside debris recently washed up on the banks of the River Thames. Hierarchy affiliated with value is discarded, emotional attachment sacrificed and the resulting tapestries become a means of presenting abstract yet meaningful information about form and the qualities of materials. Each object in these tapestries is a clue to a specific history but the jumbled, declassified presentation suggest other possibilities of history.

Through these works Bailey-Barker questions his own relationship to time and memory presenting the possibility of the co-existence of the past, present and future.

FIELDWORKS GALLERY

274 RICHMOND ROAD E8 EQW

Ruins And Relics Trawled From The Thames Find New Life in Sol Bailey-Barker’s Powerful Show

“FOR YEARS THESE OBJECTS ACTED AS TRIGGERS TO MY OWN MEMORIES OR PORTALS TO OTHER PEOPLE’S – THEY ARE GATEWAYS TO THE PAST”

Words Aindrea Emelife

The art of collecting takes many forms. Within the trade, collections are more often the preserve of a lucky few, made in the pursuit of a profit. But outside the art world, objects are usually hoarded as a result of passion – think scrapbooking, comic book and card collections, trading Pokémon stickers in the playground, yawning at the thought of having to look through coins with grandad.

Sol Bailey Barker is definitely from the latter camp. “I have always collected objects and coveted remnants of history,” he explains on the site of his new exhibition, ‘Perpetuity of Ruin’ at Fieldworks in Hackney. We are standing within a fabric enclosure amongst a disconcerting trove of artefacts and sculptural works.

“For years these objects acted as triggers to my own memories or portals to other people’s, in this way they are gateways to the past. The entire space is shrouded in raw cotton, which I hand-stitched together with red thread to create a shrine that is a womb like space, or perhaps a giant tent in a desert, a place existing outside of time.”

Bailey-Barker is catching the attention of art aficionados, primarily with his sculpture works – this is the third show in the same number of months I’ve seen his work feature in. A nomad at heart, he found some of the artefacts in the exhibition in faraway lands – but others come straight from the River Thames.

“Something about pulling objects from the riverbank and bringing them straight to my studio which was near the Thames allowed me to develop an immediate relationship with the objects, enshrining them, immediately seeing them as sculptural forms, rather than as nostalgic curiosities. The objects became my palette,” he ruminates. “Taking them to my studio allowed them space to speak. My studio was entirely dedicated to these found objects. I then began bringing together my own personal collection that I had been living with. It was an interesting exercise in letting go of personal histories whilst viewing them in a new context.”

Bailey-Barker’s works combine two and three-dimensional formats, and elide the modes of categorisation and the sense of ‘order’ one associates with collecting. One piece, centred upon aerodynamics, mixes ancient arrowheads with modern toy planes. Indeed, arrowheads were one of the first things man made fly, and the collectible nature of model planes and war memorabilia transcends history. As Bailey-Barker speaks anecdotally of the culture of collecting by the Thames, a centuries-old image of weathered men in fisherman’s hats trawling the riverside for debris comes to mind. Bailey-Barker, a youthful figure save for a striking streak of white hair on his slicked-back hair, is bucking the trend.

“The modes of categorisation change from piece to piece,” he explains. “For example in ‘Time’, the stone and the camera are both ways of measuring time, one through geological data, the other through photographs. The Meso American axe and the 1970s hammer are both broken tools with several thousand years between them. My aim is also to declassify objects and to understand them outside of the context of a Western colonist reading of history.”

Our human attraction to lost treasures and fossils of the past has long been explored by artists – most recently, famously, and to much divided opinion in Damien Hirst’s recent exhibition in Venice, ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable’. Though both artists share an affinity for exhibition titles that could easily be album names of emo pop-rock bands, the approach Hirst took is decidedly more kitsch, as he reinforces links with his American predecessor, Jeff Koons. Harking back to imagery of the lost Island of Atlantis, Hirst seeks to create an unbelievable history, by inter-splicing mythology and historical fact to create an odd pick-and-mix narrative of underwater worlds. Bailey-Barker’s work is more grounded in the real. There is no fantasy and no dream here – but there is an encouraging sense of wonder as we consider what else is out there and what we will and are leaving behind.

We are silent for a moment to listen to the audio work that circulates inside the cotton chamber – woven-together recordings of places from where he collected objects, manipulated to exaggerate certain frequencies for a temple-singing-bowl-like effect. As the ghostly sounds resonate, I ask Bailey-Barker about the title of the show.

“It refers to both destruction and antiquity, what we ruin and what we later cherish and preserve.The collective idea of ruin, a mystic building, lost and eroded by time, is far from the reality. Most great monuments have been destroyed at the hands of meticulously calculated economically motivated war and colonisation. Ruin is often systematic, objects are plundered and taken far from their places of origin and coveted for different reasons through the ages. Often we no longer know why something is sacred but we revere it, object become imbued with evolving beliefs that reflect our times.”

Indeed, the idea that buildings normally fade and ruin naturally is a Romantic delusion. The best preserved archaeological sites are those which have been destroyed by natural forces, such as Pompeii. We borrow from the past and repurpose everything, taking the walls of great castles to build sheep pens, melting the gold from South America, deforesting England’s ancient woodlands to build ships for the British Empire. And so ruins are repurposed again in Bailey-Barker’s tapestry-canvas works and sculptural forms.

Four great colossal sculptures make their homes in the corners of the space like modern totem poles. These works, made from welded and hammered airplane grade steel and fused onto shamanistic black wooden bases, are what Bailey-Barker has become known for. The pieces refract light and tinkle ritualistic sounds when tapped by your knuckles, like gongs. Both tapestry and objects are in conversation in this intimate space. “The canvasses are made from the sculptures and the objects on the canvasses form the sculptures, they are one and the same,” Bailey-Barker agrees. “When creating these sculptures I gathered the steel filings that result from the cutting process. I stored these in jars and later used them to create the base layer of the tapestries. The sculptures evolved from studies of the objects sewn to the canvasses and the new forms forged through their assemblage. The sculptures are like spires reaching up to pierce the billowing fabric of the ceiling.”

Bailey-Barker has found new life in the detritus of what we leave behind. Pieces of bone, Medieval soup ladles and remnants of Victorian age tin cans, all identified by the Museum of London, are elevated to relic status. Relics of lives once lived, of times once past, and the perpetuity of ruins reborn.